Thank you Stephan Kinsella for your comments on my blog post about your approach to rights theory. I'm not proposing an alternative rights theory. I accept the same Hoppean rights theory as you. My point is that one assumption you make- that rights must be acquired- is an error and inconsistent with the rest of your own theory because the meta-ethical norms that determine rights logically entail self ownership from the very beginning of life. You can't have an indeterminate period where a human doesn't own their own body, and then somehow comes to own it. That's inconsistent with meta-ethical norms. They can't homestead it, as you yourself have noted. Also, one cannot have a consistent rule whereby others determine when a child attains self ownership by others choosing to recognise it, since that would be a rule allocating self ownership rights by fiat, not by objective rules. The only consistent, objective rule is the universal one that each individual has the best claim to their own body from the beginning.

Below is a response to your specific comments, but I welcome a discussion of this if you are open to it:

it's not clear what he disagrees with in my conclusion.

I disagree that an individual's self ownership right is only acquired once recognised by fiat by someone else at some vague and unspecified point in the early life of that individual. Human beings have rights from the moment that an individual human being exists. That is the only position consistent with the rest of Hoppe's (and your) rights theory.

Does he thinks that we do not have rights at all, or that we never acquire them?

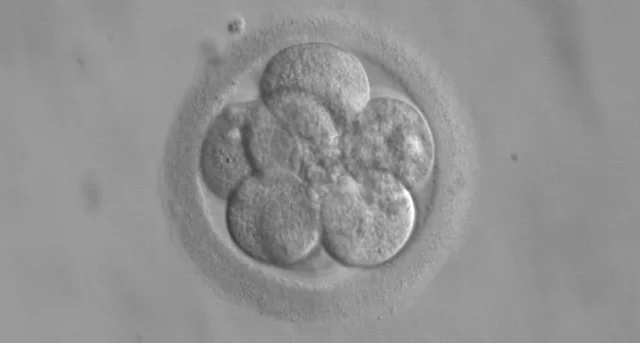

Neither, obviously, since this is a false dilemma. I think we have rights from the moment we come into existence. If you really want, you could say we "acquire" rights when we "acquire" a body (at conception), but it would be incoherent to use that word in that context since nobody is obtaining rights for themselves in the same way that nobody obtains a body for themselves- we just have one from the start.

I'd be curious to see where he thinks my motivated reasoning was wrong, or what about it is incorrect other than how I got there.

Your presumption that rights are acquired conflicts with your own theory of rights (after Hoppe). Your theory has a number of clear implications that you yourself have set out:

- The individual with the best objective claim to a body is the body's inhabitant himself.

- One cannot homestead one's own body, since one has to have a body to do the homesteading. So you can't "acquire" ownership of yourself.

- If ownership only comes into effect because it is "recognised" at some point by someone else, that would be by fiat. Such a rule is not objective, not intersubjectively ascertainable, and would be conflict promoting (invalidating it as a norm).

- Any theory of rights must always give a definitive and intersubjectively ascertainable answer at any point in time as to who owns what. There cannot be any ambiguity otherwise it fails to prevent conflict (which is the whole point of rights).

The only rule that prevents conflict over scarce resources about body ownership is self ownership from the very beginning. Any rule which involves a human not owning themselves and then at some vague and ill-defined point owning themselves is inconsistent with all 4 above.

I think a case can be made for rights, that they have to do with our nature as rational agents, and so on.

Hoppe and you have already made a case for rights: rights are the rules humans use to avoid conflict over scarce resources. Why should we have rights? To avoid fighting. What if someone disagrees with rights? Then they are contradicting themselves in the very process of arguing that position. What if someone doesn't care about justification and just wants to fight? Then they are merely a practical problem and no discussion is necessary. What is missing from this "case" for rights that Hoppe and you have already made? You simply don't need this vague stuff about based on rationality. Argumentation ethics has given rights a far clearer justification.

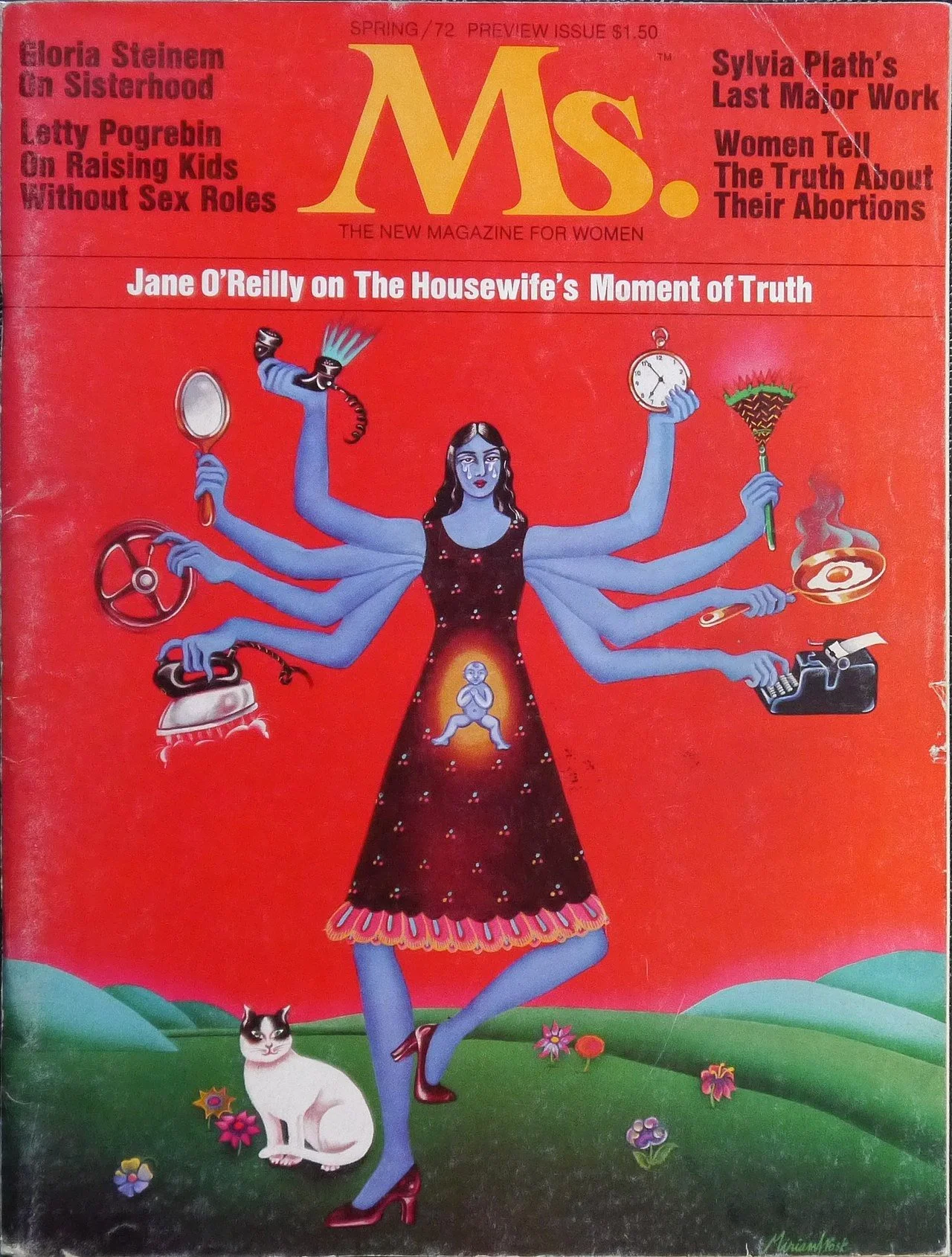

You also don't seem to realise that the logical implication of basing rights on rationality is Peter Singer's position that newborn infanticide is legitimate because newborns are not rational actors, not cognitively capable, etc. If you argue for acquired rights on the basis of rationality/cognitive ability/language/etc, you must accept the legitimacy of infanticide as that is the logical implication of your position. This is openly recognised by the more consistent pro-choice philosophers. Some, like David Boonin, just uncomfortably acknowledge the problem and move along swiftly. Others, like Michael Tooley and Peter Singer, choose to bite the bullet and accept that one cannot deny the legitimacy of infanticide if one accepts the legitimacy of abortion. Your acquired rights argument logically entails this position.

I was talking to libertarians who already accept humans (a) have rights, and that (b) they must have them for some reason, and thus, (c) they must arise at some point.

There is no logical reason that we must presume that you come into existence without rights and then acquire them. That is just an unwarranted assumption.

If you want to deny humans have rights, that rights can be justified, or that aggression can be justified, or that we have right but never acquire them or that we have them for no reason at all…. okay, let's see it. Have at it.

Um what? Obviously I don't deny rights or support aggression. I agree with 99% of your views on rights, just not your argument that rights are acquired.

Rights are justified since denying them results in self contradiction. We have rights to avoid conflict with each other: that's the "reason". We can only avoid conflict if we start with the presumption of rights for everyone (and rights are only denied with due cause). It has to be a universal rule to be workable. So humans have rights from the moment an individual comes into existence. What's missing from that?

I do not know what he means that rights are inherent. Inherent in what? In being human? What about other forms of intelligent life?

Yes, of course inherent in being human. We are humans discussing this, trying to live together without conflict, so obviously we are talking about human rights. We are not debating with monkeys and sharks about how to come to a peaceable coexistence. Rights only arise as part of argumentation among humans about how to get along in a world of scarce resources without fighting. Inherent doesn't entail given by a god or anything, it just means rights must be presupposed for all humans who have not committed any crime.

So, yes, we are humans arguing about this, and we are making rules for humans. There are no donkeys or whales involved in this debate. The rules we agree for peaceful coexistence must be objective, i.e. intersubjectively ascertainable. It so happens that one must include all humans in these rules- they must be universal rules- to meet this criterion. So rights do apply to all humans, not just those engaging in the rational debate about rights. That includes humans when they are babies, foetuses, or zygotes.

Contrary to your assumption, this does not imply that intelligent aliens would not have rights. If we could negotiate with intelligent aliens about how to live in peace, then they would have rights. Again, this would mean that those rights would have to be universal, so the babies or eggs or nymphs, or whatever form undeveloped aliens take would have rights, even though those babies would not yet be developed enough to argue a syllogism and demonstrate rationality. Would you argue that only the adult aliens (the ones capable of reason) have rights? Would the baby aliens be fair game for us to hunt and kill? If not, then you're not really basing it on rationality, are you? You're basing it on membership of the species that contains members who are capable of agreeing objective property rights.